What’s New at Wildlands

Human History of Wildlands: Pudding Hill Reservation

Chandler’s Pond at Pudding Hill Reservation in Marshfield.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Pudding Hill Reservation in Marshfield was donated to Wildlands Trust in 1991 by Elizabeth Bradford. Though relatively small at 37 acres, the preserve has a varied terrain, including an upland ridge, frontage on Chandler’s Pond (from which a bubbling brook becomes the South River), and the 128-foot Pudding Hill itself. A mowed 0.4-mile trail provides easy access to the preserve from the parking area on Pudding Hill Lane. Today, Pudding Hill Reservation offers visitors a relaxing sanctuary just minutes from Marshfield Center.

As with many of the properties featured in this “Human History of Wildlands” series, the present-day tranquility of the area belies the long human impact on the land in and around Pudding Hill Reservation. Like Hoyt-Hall Preserve and Phillips Farm Preserve, other Wildlands properties in Marshfield, this land has been in constant use for generations, including Native Americans for thousands of years and European settlers over the last four centuries. With human habitation comes change.

The North and South Rivers have always been heavily utilized by Native people, including the Massachusett Tribe, for hunting, fishing, and shell fishing, and as water highways for transport and trade throughout Southeastern Massachusetts.

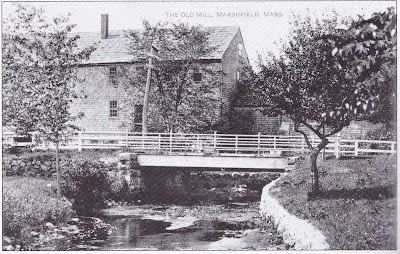

Marshfield’s first gristmill, founded in 1654 by William Ford and Josiah Winslow. Photo circa 1940. The site is now Veterans Memorial Park, directly adjacent to Pudding Hill Reservation. Via North and South Rivers Watershed Association.

After 1620, Pilgrims from the Plymouth Colony were quick to see these benefits. Settlers began to arrive in Marshfield before 1640. As you will remember from other installments of this series, one of the first orders of business in areas with flowing water was the building of mills—especially gristmills. With this goal in mind, Samuel Baker, John Adams, and James Pitney purchased the Pudding Hill property along the South River. By 1659, Samuel Baker's gristmill was up and running, made possible by the damming of the South River to create Chandler’s Pond. Other dams and mills followed in 1706 and 1771.

But bigger things were on the horizon. In 1810, as the Industrial Revolution was beginning, waterpower was once again instrumental in the establishment of the Marshfield Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company. A network of support enterprises helped the company thrive through the first half of the 19th century. Leavitt Delano's blacksmith shop and Elijah Ames' carpentry shop, among others, produced barrels, tools, and other necessities. Other factories produced textile dyes. Farming was largely replaced by factory work, which necessitated housing, boarding houses, a store, and a school.

However, the second half of the 19th century was the time of "Manifest Destiny," and throughout New England, the opening of the American West drove a significant emigration of local farmers to the Great Plains and beyond. In addition, larger manufacturing cities such as Brockton, Lowell, and Lawrence drew workers away from the smaller towns. The Cotton and Woolen Company closed in 1860, but later Gilbert West purchased the water rights to the property and ran a saw and gristmill until the 1920s.

Camp Milbrook campers swimming in Chandler’s Pond in 1967. Via UMass Boston, Joseph P. Healey Library.

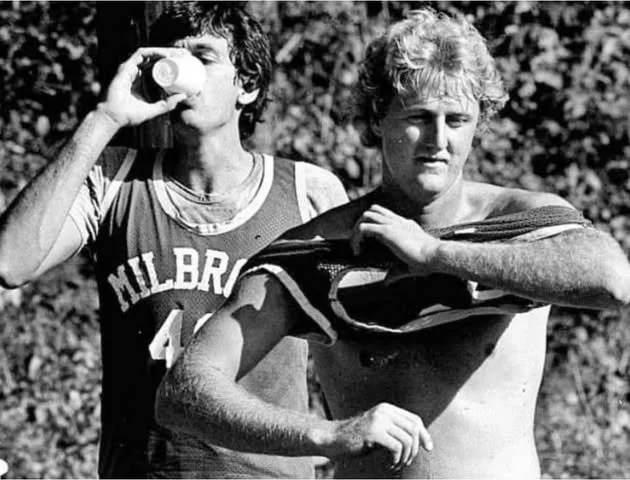

Marshfield was gradually becoming the seaside vacation and bedroom community of today. In the 1920s, Pudding Hill and Chandler’s Pond became the summer home of the Bradford family. In the 1950s, the Bradfords moved in full-time. In an interview, Elizabeth Bradford, a direct descendant of Plymouth Colony governor William Bradford, relates the history of Pudding Hill as a quiet, peaceful refuge—not just for her family, but for many others. From about 1938 to 1985, Pudding Hill was the location of Camp Milbrook, a summer camp that served hundreds of children over its lifetime. It also gained local fame as a training camp and teaching clinic for the Boston Celtics, where coach Red Auerbach and stars like Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, and Robert Parish taught basketball fundamentals to summer campers.

After the camp closed, the Bradfords started thinking about what would happen to the property they loved. Housing and other development was erasing much of the historic farmlands and woodlands in town, and Elizabeth Bradford was committed to saving Pudding Hill and preserving its beauty. In 1991, she donated it to Wildlands Trust. Today, it is a popular destination for hikers, bird watchers, and nature lovers who use its trails and open space for all the outdoor activities that Ms. Bradford intended. It will remain as such forever under Wildlands’ stewardship.

Kevin McHale and Larry Bird at Camp Milbrook. Video: Red Auerbach instructs kids at Camp Milbrook in Marshfield in 1974. Source: GBH Archives.

We hope you will take advantage of what Wildlands Trust offers in Marshfield and throughout Southeastern Massachusetts. Please come and visit. To learn more, look over the following resources used in researching this article:

The Power of Water: Milling and Manufacturing in the North River Valley by Kezia Bacon, NSRWA, April 2008.

An excellent piece that delves more deeply into the history and stories of the entire North and South River watershed, including several other areas that Wildlands preserves, such as Hoyt-Hall Preserve, Cushman, Preserve, Willow Brook Farm, Tucker Preserve/Indian Head River Trail, Phillips Farm Preserve, and Cow Tent Hill Preserve. I thank Ms. Bacon for writing it and hope you will enjoy reading it.

Marshfield: A Town of Villages 1640 - 1990, by Cynthia Hagar Krussel and Betty Magoun Bates, Historical Research Asociates,1990.

Interview of Elizabeth Bradford, by Kezia Baker, WaterWatch (the newsletter of the North and South Rivers Watershed Association), Sep. 1993.

North and South Rivers Watershed Association website: www.nsrwa.org.

Pudding Hill Reservation, Wildlands Trust: wildlandstrust.org/pudding-hill-reservation.

As always, a special thanks to Thomas Patti for editing this piece.

Human History of Wildlands: Old Field Pond Preserve

The cranberry shack at Old Field Pond Preserve once housed the bog supervisor.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Old Field Pond Preserve is a 145-acre property on Bournedale Road in the town of Bourne. It boasts a wide variety of features—ponds, fields, wetlands, and forests. Wildlife including waterfowl, deer, coyotes, small game, and endangered northern red-bellied turtles are abundant. Rare plant life, such as the Plymouth gentian and carnivorous sundew, find refuge here. It is a truly wonderful place.

Readers who are familiar with Wildlands’ properties might never have visited or even heard about Old Field Pond Preserve. Although it is one of Wildlands’ most beautiful properties, it has no open public access, so Wildlands does not highlight it on its website. The preserve is "landlocked" by private property. Although there is no parking and visitors may not walk in on their own, there are many opportunities to enjoy the property. More on this later.

Like the Winslows in last month's history of Hoyt-Hall Preserve and the Barkers of Willow Brook Farm, Old Field Pond Preserve’s history is as much about a family as it is about a parcel of land. Whenever a family is associated with a landscape over a long period of time, their imprint is palpable. You'll see this clearly in the story of the Ingersolls.

Hike & Hops at Old Field Pond Preserve in November 2023.

Early history

As the glaciers retreated about 12,000 years ago, meltwater flowed south and created a myriad of rivers and streams in the outwash plains. Native Americans soon took advantage of the opportunities for fishing and shellfish and settled the area that they called Comassakumakanit. What was known as the Manomet River by the Natives and Monument to the English flowed from Great Herring Pond into Buzzards Bay. As its name indicates, Great Herring Pond was rich in herring, and its banks were moist and fertile to farm. The area was and still is home to the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe.

The Tribe continues to own 400 acres near Old Field Pond Preserve. Chamber Rock, Burying Hill, Wishing Rock, and Sacrifice Rock are all local features of cultural and historical significance to the Tribe. This year, scientists used ground-penetrating radar to locate old Wampanoag burials at Burying Hill, providing new evidence in support of the Tribe’s oral history dating back centuries. The Herring River Trail, now called Herring Pond Road, and Bournedale Road are important ancient thoroughfares still in use today.

Historical plaque at Burying Hill, near Old Field Pond Preserve in Bourne. In addition to a burial ground, the area was the site of the first meeting house for Native Americans in Plymouth Colony.

European settlement

At the mouth of the Monument River, about a mile from Old Field Pond Preserve, is the Aptuxet Trading Post, founded in 1627 by the Dutch from New York and the Plymouth Pilgrims. It is reputed to be the first such post in New England and the site of the earliest recorded use of "Wampum," beads made from quahog clam shells as currency.

As Plymouth Colony expanded south to Cape Cod, the first town to be established was Sandwich in 1637. The area now known as Old Field Pond Preserve was in the western section of town. Among its first settlers was Colonel John Bourne, patriarch of a family influential in the area for the next 250 years. In 1695, the Herring River Grist Mill was built. Timber, shipbuilding, farming, salt hay production, fishing, and glassmaking were the principal industries for the area, with cranberry production becoming increasingly important along the way.

In the 1780s, the main house on the Old Field property was built and occupied by the family of Jonathan Bourne. It was also the site of the West Sandwich post office. By the late 19th century, other businesses grew in the area, including the Holway Axe Factory and the Keith Car Works. A railroad line also served the area. The growing community soon decided to break away from Sandwich, and in 1884, the town of Bourne was incorporated.

At about this time, the area surrounding Old Field consisted of a large section of woods and farmland. It was known as Colonel Horton's Fishing Club, a private enterprise catering to the emerging summer tourist industry. Change was on the horizon. The Monument River was to disappear as work on the long-contemplated Cape Cod Canal began. Completed in 1914, the canal split Bourne in half, putting the area's fishing industry in jeopardy. So that the Cape wouldn't become an island, three bridges were built, one for trains and two for ground transport. The Bourne Bridge will soon come into play in this history.

The Ingersoll era

Kahlil Gibran’s sketches of 14-year-old Hope Ingersoll while staying at Bay End Farm in 1918. Via kahlilgibran.com.

In 1906, the fishing club was sold to the Garland-Ingersoll family, led by Mary Tudor Garland Ingersoll, who immediately transformed the 900-acre lot into Bay End Farm.

Mary and her husband were wealthy socialites. Mary was a well-known and passionate patron of the arts. She immediately set out to create a place for artists to stay, inspire each other, and create. She had prefabricated cottages built for artists of all kinds to visit, several of which are still in use today. Mary, a close friend of painter Georgia O'Keeffe, played host to many notable figures of her time, including Mark Twain and artist and writer Kahil Gibran, who wrote part of his famous book The Prophet while residing at the farm. The artist's colony flourished until the 1950s. The property was also made available to provide housing for military officers during World War I.

Postcard depicting Bay End Farm in the early 1900s.

Mary's other passion, and one carried on and championed by her daughter, Hope Garland Ingersoll, was the preservation of their farm, one of the last large properties in the area. At some point, Hope changed the name of Bay End Farm to Grazing Fields Farm. The property became well-known for its progressive land use, eschewing pesticides and herbicides, and for its livestock breeding, famous for its prize-winning Welsh ponies, Guernsey cattle, Montdale sheep, and Sealyham Terriers.

Grazing Fields Farm exists today as a horse farm on a portion of the Ingersolls’ original property.

Grazing Fields Farm operated in this manner until 1957, when Hope Ingersoll gained local and even national fame during her 25-year fight to save the property from a state highway expansion. The project’s goal was to speed up summer automobile access to the Bourne Bridge. Officials would have invoked eminent domain to break up the Ingersoll property. Hope contested the state's architectural plan and privately paid architects to design an alternative route plan. In 1982, aided by new federal environmental regulations, Hope prevailed. The story gained recognition throughout the environmental movement and in the news, including the New York Times, whom Hope told, “I think it’s true that you can fight City Hall. But you’ve got to have a lot of persistence, and help—and luck. We started this long before anyone was worried about the environment. … We have always been concerned with protecting the land.”

Hope Ingersoll. Photo courtesy of Kofi Ingersoll.

Old Field Pond Preserve

In 1983, the Ingersoll family decided to donate 145 acres in the middle of their property to Wildlands Trust so it could be protected in perpetuity. This was the beginning of Old Field Pond Preserve. The name Grazing Fields Farm applies today to the horse farm on the southeast side of Bournedale Road. The rest of the historic Ingersoll land, abutting Old Field Pond Preserve on the northwest side of Bournedale Road, has reclaimed the name Bay End Farm. Hope’s grandson, Kofi Ingersoll, owns and operates this organic produce farm. In partnership with the Ingersoll family, Wildlands uses Old Field Pond Preserve in several ways. Wildlands and Bay End Farm staff and volunteers guide hikes on the property throughout the year. The farm also provides environmental education to Wildlands’ Green Team, Envirothon Team, and other youth programs, and assists Wildlands staff in the maintenance, trail trimming, and haying of the preserve.

We hope you will join us for our next guided hike or volunteer event at Old Field Pond Preserve. Sign up for our E-News and visit wildlandstrust.org/events to stay updated on the latest opportunities to explore this special place. You will not regret it.

Kofi Ingersoll. Photo by Drew Lederman.

Learn more

Resources utilized in researching this history include:

The Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe: herringpondtribe.org

Bourne Historical Society: bournehistoricalsociety.org

American Aristocracy: americanaristocracy.com

Grazing Fields Farm: grazingfields.com

Kahil Gibran website: kahlilgibran.com/latest/132-the-house-of-the-prophet-gibran-at-mrs-garlands-farm

"Farmer Wins 25 Year Fight over Cape Road," New York Times, 10/10/82: nytimes.com/1982/10/10/us/farmer-wins-25-year-fight-over-cape-road.html

50 Remarkable Years, 50 Remarkable People, “The Ingersoll Family,” Wildlands Trust: wildlandstrust.org/anniversary-book-blog/2024/4/9/ingersoll-family

Interview with Kofi Ingersoll, 10/31/25.

A special thanks to Kofi Ingersoll for his recollections and photos, and to Thomas Patti for editing this history.

Human History of Wildlands: Hoyt-Hall Preserve, Marshfield

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Hoyt-Hall Preserve in Marshfield is one of Wildlands Trust's most popular preserves. Acquired in 2000, the property was quickly designated as a "showcase" preserve owing to its diverse woodland and wetland habitats and associated wildlife. Containing 123 acres and bordering 82 acres of additional conservation land, Hoyt-Hall protects a significant assemblage of open space in a growing town.

Yet there is another story here. Hoyt-Hall's human history spans over 10,000 years of settlement and change. Archeological evidence shows that Native people followed the retreating Laurentide ice sheet north, first as nomadic hunters and soon as settlers. Remnants of permanent dwellings have been excavated in Marshfield, dating back at least 3,000 years. The area that now contains Hoyt-Hall Preserve was partly a saltwater marsh with access to the ocean, and shell deposits show that it was well utilized by the Natives for fishing. By 1600, it was used seasonally by the Wampanoag Tribe as a summer home to take advantage of these resources. They wintered on the lands known today as Lakeville and Middleborough. The Wampanoags called the present-day Marshfield area "Missacautucket," and Massasoit was their powerful sachem.

Swans on Long Tom Pond. Photo by Mike Arsenault.

The Value of Relationships

Upon the Pilgrims’ arrival to Plymouth Harbor, settling on lands outside the Colony's patent was prohibited. Early on, a few colonists managed to do so anyway. One was William Green in 1623, who established a commercial fishing post on what is now known as Green's Harbor. But general settlement was not permitted until 1632, when land grants began to be awarded. In 1636, Plymouth Colony governor Edward Winslow was granted a large tract of land, including the current Hoyt-Hall property. The Winslow family, along with the whole Plymouth Colony, was successful, due in large part to the strong relationship between Governor Winslow and the Wampanoag leader Massasoit, which endured for nearly half a century. More on the importance of relationships history later.

In 1637, the Pilgrim Trail, then called Green's Harbor Path, was the first general court-ordered road in the Colony. It passes along the border of Hoyt-Hall Preserve, as does King Philip’s path, an ancient and famous Native trail. Three Winslow family homesteads were built on the Hoyt-Hall property, much of which remained with the family until 1822. Two colonial governors, Edward and his son Josiah, lived and prospered on the land, as did Edward's adopted son, Peregrine White. White was born in 1620 on the Mayflower, becoming the first Englishman to be born in America.

In 1640, the Town of Marshfield (initially called Rexhame) was incorporated and grew quickly with new settlers. While many surrounding towns suffered much death and tragedy during King Philip's War in the 1670s, Marshfield remained relatively unscathed due to the Winslow family's strong relationship with the Wampanoag Tribe.

Hoyt-Hall Transformed

Because much of Hoyt-Hall was then tidal marshland, in 1675 a dam was built to create Long Tom Pond (named after a local Native who was killed in King Philip's War), providing a freshwater source first for general farming and later for cranberry growing.

Historic Winslow House. historicwinslow.org

The Revolution

Directly adjacent to Hoyt-Hall Preserve is the Isaac Winslow house. Built circa 1699, it is the oldest home in Marshfield. Isaac was a well-known physician with a reputation for serving both settlers and Natives. He inoculated many against smallpox and other diseases in the early 1700s. However, as relationships between the colonists and the English crown deteriorated, the Winslow family became well-known Loyalists, and Isaac's house became a Loyalist meeting place. Relations between the Patriots and Loyalists were tense, and the Loyalists pressed for British troops to be brought in to protect them. A force of 114 troops landed, but fighting was eventually avoided, once again as a result of the Winslow family’s strong relationships with their neighbors.

Home of a Statesman

After the war ended, the Winslow family continued farming the property until 1822, when it was broken up and sold to a series of families. Some of the property returned to woodland, and some went to cranberry production. Some of it was sold to Daniel Webster, noted U.S. Congressman and Secretary of State, who lived in Marshfield from 1832 until his death in 1852. In 1884, Walton Hall purchased the Webster estate. In 1928, about 1,000 acres were purchased by Lincoln Hall, who converted some of the woodlands to cranberry bogs, which remained in production until the 1960s. During this time, the land began to take on the scenic character that we see today.

Daniel Webster Estate in 1859, as depicted on a 1909 postcard. From Patrick Browne, “The Almost-Battle of Marshfield.”

Protected Forever

In 2000, the land was sold to Wildlands with the assurance that it would be preserved in perpetuity, with beautiful trails for visitors to explore. In 2016, with funding from the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Recreational Trails Program, a 1.75-mile trail loop was completed, with a parking lot on Careswell Street (Route 139). Today it is one of Wildlands’ most popular preserves, with many families enjoying this remarkable and historic property every year. Along with the adjacent Historic Winslow House, Hoyt-Hall Preserve's scenic beauty is forever linked to its rich history.

Back to Relationships...

So, you'll remember my earlier mention of the importance of relationships in the history of Hoyt-Hall Preserve. We too often think of the past in terms of events; i.e. wars, discoveries, and the like. We should not forget that nearly all historical events are either tempered or exacerbated by the human relationships that surround them. Had the Pilgrims not developed a strong relationship with Massasoit, Plymouth Colony would likely not have survived its first year. Fast forward 50 years, and it's clear that many lives were lost due to the souring of this relationship during King Philip's War. Be good to your friends.

Hoyt-Hall Preserve. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

Learn More

To learn more and visit Hoyt-Hall Preserve, explore wildlandstrust.org/hoythall-preserve. The following resources were utilized in researching this history:

“Books and History Converge at Hoyt-Hall: Former Landowner Honored by Family” by Amy Markarian, Wildlands Trust, 2022.

The Historic Winslow House: winslowhouse.org.

History of Marshfield Massachusetts by Lysander Salmon Richards, 1901.

“The Almost-Battle of Marshfield” by Patrick Browne, 2011.

“History of Marshfield,” Kiddle Encyclopedia.

“Our Story Not Theirs” by the Mattakeeset Tribe.

A special thanks to Mike Arsenault, Amy Markarian, and Thomas Patti for their assistance with this piece.

Human History of Wildlands: Cow Tent Hill Preserve

River overlook at Cow Tent Hill Preserve. Right: Helen Philbrick, who in 1994 donated Wildlands’ former headquarter property in Duxbury.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Throughout this “Human History of Wildlands” series, I have discovered time after time that in Southeastern Massachusetts, a land does not have to be large to be full of history. Cow Tent Hill Preserve in Duxbury is my latest example. Within 32 acres, the preserve encompasses a tidal creek, Duck Hill River, salt- and freshwater marsh, and wooded upland in Duxbury's Millbrook neighborhood.

Early History

For over 10,000 years, Native peoples inhabited this area, drawn by opportunities for hunting, fishing, and shellfishing and access to nearby Duxbury Bay and trading routes like the North River. The Wampanoag Tribe, who lived in the area, called their home Mattakeesett, meaning "place of many fish." They, like other Native peoples living on the New England coast, thrived for many generations, as evidenced by the area’s 33 archeological sites recognized by the Massachusetts Historical Society. However, in the early 1600s, Natives came into contact with increasing numbers of European fishermen and trappers—and in turn with illnesses such as small pox, for which they had no immunity. Between 1600 and 1618, it is estimated that 80 to 90 percent of the local Native population died.

Consequently, when the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, they found relatively few Natives, but large areas of cleared fields ready for agriculture. It is said that Duxbury had as few as four Native families by 1620.

The Harry and Mary Todd Trail at Cow Tent Hill Preserve in Duxbury. Harry and Mary Todd also supported the protection of Willow Brook Farm in Pembroke, where another trail bears their name.

European Colonization

After a difficult start, many colonists followed the Mayflower to Plymouth Colony. Soon, the colony outgrew its original lands. In 1627, the contract with London investors that had funded the initial colonization expired, and leaders of the colony, such as William Brewster, Myles Standish, and John Alden, began allotting nearby lands to colonists. Brewster, Standish, and Alden all received lands in Duxbury. In 1639, Duxborrow (the town's original name) became the colony’s first incorporated town, after Plymouth. One of its early orders of business was to approve the construction of a grist mill on Stoney Brook. As the town grew, a fulling mill and textile mill were added. Stoney Brook became known as Millbrook, where a thriving village took root.

An aside here... Another early resident was Robert Mendame, who owned the land that became the site of the grist mill. His wife, Mary, is immortalized—unfortunately and perhaps unfairly—by an item in the Colony Court Records, which became Nathaniel Hawthorne's partial inspiration for The Scarlet Letter. It was recorded that Mary had a "dallyance" several "tymes with Tinsin, an Indian," and was to be "whipt at a carts tayle through the townes streets."

Others moved in after the initial Pilgrim settlers. One of note was Edouard BonPasse, an ancestor of the Bumpus family who bequeathed the Cow Tent Hill property to Wildlands Trust. Captain Benjamin Church also lived there in the years leading up the King Philip's War, where he became a renowned military leader.

Crab Island House, built 1646. When Constant Southworth became the second owner of the Stoney Brook grist mill in the 1640s, he moved to this house, which was included in the purchase. Three generations of Southworths operated the grist mill. It was rebuilt it in 1746 and went out of business in the late 1800s with the arrival of the railroad in Duxbury. Constant Southworth was the son of Alice Carpenter Southworth, who married Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford. Photo from Wentworth 1973 (see “Learn More”).

Post-Colonial Period

In the 18th and 19th centuries, industry flourished in Millbrook. Notable businesses included the Duxbury Woolen and Cotton Manufacturing Co. and the Ford Store, reputed to be the first department store in America. A rail line was also opened to transport these products to market. However, around 1900, the mills and businesses of Millbrook closed, unable to compete with the burgeoning textile manufacturing industry in Massachusetts' larger cities. But Duxbury's popularity as a vacation destination and residential community grew.

Cow Tent Hill Preserve.

What had once been called Stoney Brook and then Millbrook was then renamed to Duck Hill River. It returned more or less to the woods, fields, and marshes of 300 years earlier. The property became known as Cow Tent Hill because once it returned to pastureland, farmers would erect a canvas tent to provide shade for the grazing cattle during the heat of summer. As Duxbury became an upscale residential community, most farming also fell by the wayside. Yet the town strove to maintain its rural character, protecting over 3,000 acres of woods and marshland. In 1985, Wildlands Trust opened Cushman Preserve, donated by the granddaughter of Captain David Cushman, Jr., who had purchased the land from relatives of his wife, a direct descendant of John Alden. In 1999, Beatrice Bumpus bequeathed Cow Tent Hill Preserve to Wildlands.

A series of photographs of Cow Tent Hill from 500 years ago to the present would tell a story of stark landscape change. The area would have looked very different before and after 1620, when the Pilgrims first laid eyes on it. Fast-forward 150 years, and booming industry would have depicted a place transformed by people and time. Today, Cow Tent Hill has come close to full-circle, implying a pristine, uninterrupted past to the untrained eye. Yet human beings have always interacted with these wildlands.

We have not located these pictures, but that does not mean they do not exist. If you have photographic or any other evidence of Cow Tent Hill Preserve’s varied past, please reach out at communications@wildlandstrust.org.

We encourage you to visit the preserve for yourself. A property description and directions are available at our website: wildlandstrust.org/cow-tent-hill-preserve.

Learn More

If you would like to learn more about the human history of Millbrook's Cow Tent Hill Preserve, below are some of the resources that contributed to this piece:

The Settlement and Growth of Duxbury, 1628 to 1870, by Dorothy Wentworth, 1970.

A History of The Town of Duxbury, by Justin Winsor, 1849.

Wildlands Trust Cow Tent Hill Management Plan, 2011.

North and South Rivers Watershed Alliance: nsrwa.org

The Duxbury Rural and Historical Society: duxburyhistory.org

Human History of Wildlands: Brockton Preserves

Stone walls traverse the woods at Brockton Audubon Preserve. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Back in 2018, Wildlands Trust President Karen Grey addressed an audience of land conservation professionals, town conservation commission members, and volunteers at the Southeastern Massachusetts Land Trust Convocation. Though Karen spoke broadly about Wildlands’ land protection, stewardship, and education initiatives, most of the audience’s questions and comments came when Karen described Wildlands’ activities in the city of Brockton. It was clear that many listeners were surprised that Wildlands would invest so much time and effort in the state's sixth-largest city of over 105,000 residents. Karen asserted that land conservation is an important goal anywhere, and perhaps even more so in a city where natural and recreational resources are limited.

To help a city reconnect with its long-lost natural resources, we first need to understand its history. How have humans altered the landscape over time? What exactly has been lost? Only by knowing an area’s past can we begin to repair its future.

Wildlands is lucky enough to work with someone who has witnessed Brockton’s history firsthand, who can share local stories that might otherwise have been forgotten. Since 2020, Frank Moore has protected his 20-acre farm and forest property in East Bridgewater through a Conservation Restriction (CR) with Wildlands. But in the 1930s and ‘40s, Mr. Moore spent his childhood in Brockton, where the lands of present-day Stone Farm Conservation Area and Brockton Audubon Preserve served as his “playgrounds.” In April 2024, Wildlands Land Protection Assistant Tess Goldmann and Communications Coordinator Thomas Patti visited Mr. Moore at his East Bridgewater home to hear his many stories from growing up on these lands. Mr. Moore’s encyclopedic knowledge of the area was crucial to my research for this piece.*

If you, like Mr. Moore, have oral, written, or photographic accounts to share pertaining to the natural or cultural history of Southeastern Massachusetts, we would love to hear from you. What may seem to you like trivial stories might be pivotal to our understanding of the places we strive to protect—and to our very ability to protect them.

Please contact Communications Coordinator Thomas Patti at tpatti@wildlandstrust.org to share your stories.

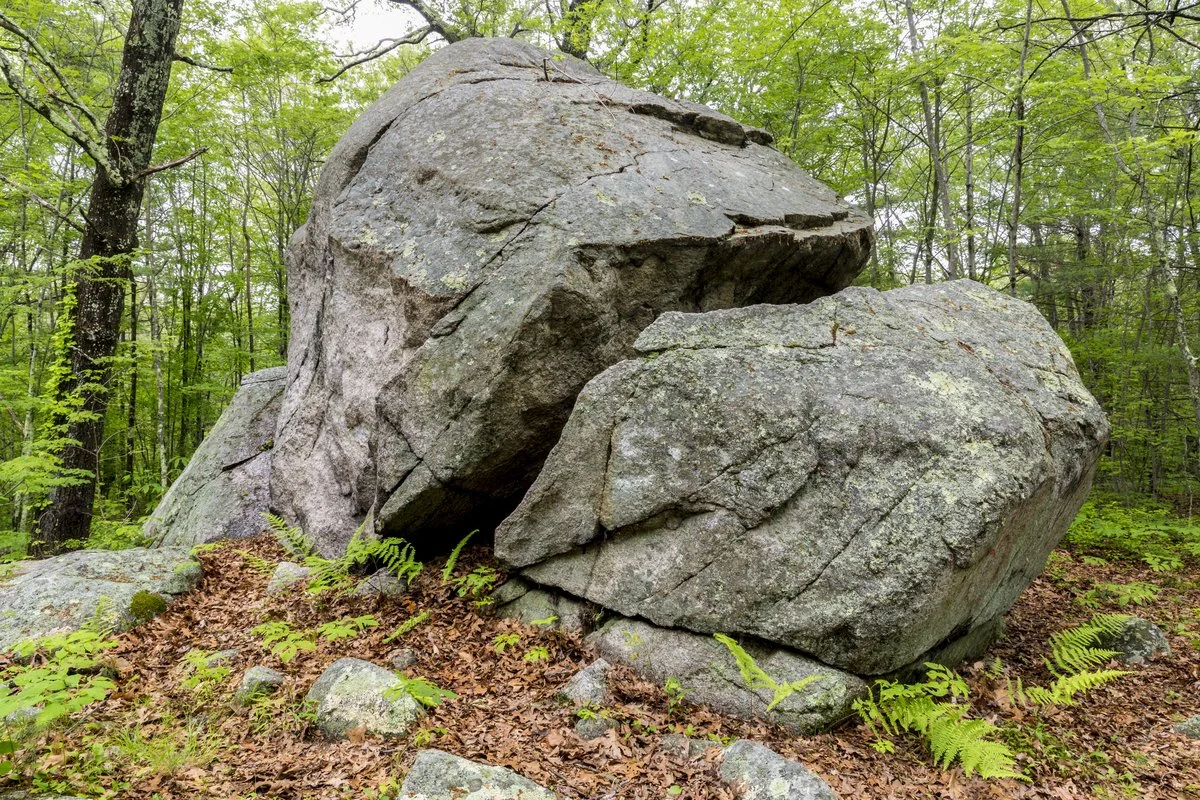

Glacial erratic at Brockton Audubon Preserve. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

Brockton’s Beginnings

Brockton lies within the Taunton River Watershed, the history of which I explored this spring. The area has a 10,000-plus-year history of habitation by native peoples, most recently members of the Wampanoag Tribe. Their population thrived, creating one of the most densely populated areas of local native settlement. According to the Wampanoag Tribe, the areas that now includes Brockton Audubon Preserve and Stone Farm Conservation Area also had religious significance, as evidenced by the rearrangement of some of the many glacial erratic boulders into formations that align with astronomical events, such as the daily and annual path of the sun through the sky.

However, in the early 1600s, exposure to disease brought by European trappers and fishermen—even before the 1620 arrival of the Pilgrims—decimated the local population by as much as 80 percent.

Then Plymouth Colony was founded, and within 20 years it had out-grown its initial settlement. In 1649, Massasoit, sachem of the Wampanoag Tribe, sold the land then known as Saughtucket to Myles Standish. It was renamed to Bridgewater, and again to North Bridgewater in 1821. The area thrived as a farming and forestry community until the mid-1800s. During the years leading up to the Civil War, the area was a well-known stop on the Underground Railroad, helping runaway slaves reach safety in New England and Canada.

But rapid change was coming. The end of the Civil War accelerated the westward migration of farmers out of New England. The Industrial Revolution was taking over, and farmers were soon replaced by immigrants from Europe and beyond, drawn by jobs in the burgeoning textile and shoemaking industries. The rapidly growing town was reincorporated as a city in 1881 and given its current name of Brockton in 1884. Interestingly, the name came from Sir Isaac Brock, a British officer in the War of 1812, who had no connection whatsoever to the town. Who'd figure?

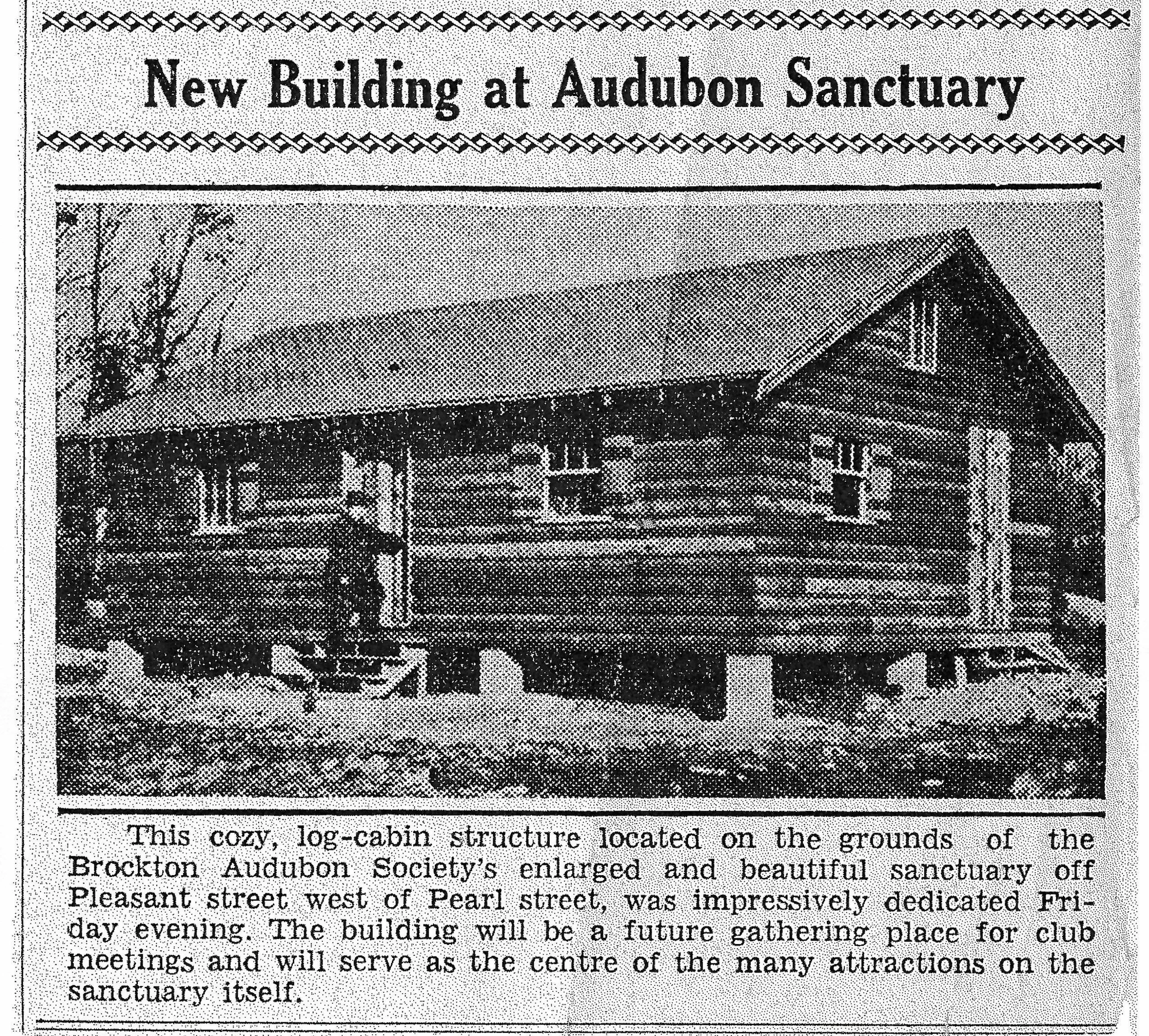

From the Brockton Daily Enterprise, April 3, 1937. “With the near completion of improvements to the new sanctuary, located off Pleasant street, the Brockton Society has one of the finest wild-life conservation areas in this section of Massachusetts. … [It] contains a diversified terrain suitable for a variety of birds and plants.” Clipping courtesy of Frank Moore.

Progress Spurs Preservation

Brockton was headed for the big time. In 1883, it gained the first municipal AC electrical power system in the world, with the first switch pulled by none other than Thomas Edison. By 1900, over one-third of Brockton’s male population was employed in the shoe industry. Growth was changing the character of Brockton. Land was developed for industry, and housing was rapidly replacing the wetlands, farms, and fields of 50 years earlier.

Wildlands Trust was not the first organization to recognize the need for environmental protection and education in Brockton. In 1919, Amelia Brown and 88 others came together to found the Brockton Audubon Society, with a mission to save wooded areas and the wildlife within them. In 1921, the Society purchased 23 acres from Martin Packard to create the first Brockton Audubon Preserve. In 1937, they added 39 acres and built a log cabin-style building known as the Clubhouse to use as a headquarters and a site for picnics and special events. In the following years, the Society, under the leadership of Brockton tree warden Rufus Carr, obtained additional parcels to bring the preserve to its current 128 acres. For many years, the land provided a beautiful and popular resource for the community. However, as the founding Society members grew older, its membership shrank, and caring for the property grew difficult. In 2011, the remaining members voted to donate the land to Wildlands Trust to ensure its permanent protection.

Adjacent to the Brockton Audubon Preserve was a City-owned tract of 105 acres known as Stone Farm Conservation Area. Over the years, this land witnessed many changes, as well. At various times, it has been a pasture, a timber plantation (until the 1938 hurricane leveled all of the pines), a horse farm, and an ice pond with an ice house. It has been the site of a Brockton police firing range and a city dump. Each successive use eventually faded into the woods and wetlands we see today. In 2018, the City of Brockton, while retaining land ownership, contracted Wildlands Trust to undertake the management of the property through Wildlands’ Community Stewardship Program. Wildlands staff completed new and restored trails in 2019, reopening the farm to the public.

Brockton High School Envirothon Team members test water quality during the 2023 Massachusetts Envirothon competition.

A Bright Future

Not done yet, Wildlands continues to work closely with the City in other areas. Through the D.W. Field Park Initiative, Wildlands has spearheaded ecological and recreational improvements in Brockton's largest and most popular open space asset. Wildlands is also working with Manomet Conservation Sciences on a NOAA grant to build outdoor classrooms at three Brockton elementary schools. Furthermore, Wildlands co-leads both the Brockton High School Envirothon Team and Green Team to engage Brockton-are youth in environmental education, stewardship, and community service.

Which brings us back to where we started. Karen Grey's message in that 2018 presentation was simple. Whether Wildlands is acquiring an urban preserve, providing resources and expertise to help a city reach its environmental goals, or advancing public education and youth development to foster long-term commitment to environmental protection, all of these initiatives flow from the same mission that drives the organization’s work elsewhere in the region. In many more affluent areas, Wildlands’ goal is to preserve the natural beauty that remains—to keep woods as woods and fields as fields. But in less fortunate areas, the time for preservation is long gone. Instead of turning its back on these communities, Wildlands proactively and holistically supports them, returning pistol ranges and dumping grounds to their historic natural conditions and helping future generations take pride and action to protect their local environment. Thus, the Wildlands mission is just as relevant in a city as it is anywhere.

Learn More

I encourage you to visit Brockton Audubon Preserve and Stone Farm Conservation Area to search for evidence of this history on the landscape. Please also explore the following sources, which I consulted for this piece:

Brockton Historical Society: brocktonhistoricalsociety.org

Wildlands Trust Baseline Documentation Report, Brockton Audubon Preserve

Brockton Public Library: brocktonpubliclibrary.org

History of Brockton, Plymouth County, Massachusetts 1656–1894. Bradford Kingman. Library of Congress.

Interview with Frank Moore. April 23, 2024. Conducted by Tess Goldmann and Thomas Patti.

* We are saddened to share that Frank Moore passed away last month at the age of 92. We extend our deepest sympathies to his loved ones, and our gratitude to Frank and his wife Rosemary for welcoming us into their home last year. Read Frank’s obituary here.