By Amy Markarian, Senior Copywriter

Read Time: 9 min

Chances are, if you’ve seen the news at all over the last several weeks, you may have heard about the now famous Steller's Sea-Eagle that paid a visit to Southeastern Massachusetts in December, and has since been putting on a show in coastal Maine. If you’re not an avid birder, and you haven’t followed this avian saga, you may be wondering why this is big news. After all, our region is fortunate to be home to a number of Bald Eagles and a variety of other spectacular birds. What, then, is so significant about this particular bird and the time it spent along the Lower Taunton River in December? To find out, we turned to two of Wildlands’ own board members, Greg Lucini and Wayne Petersen, who each offer a unique perspective on this remarkable drama that’s got everyone rooting for a magnificent, wayward bird from Russia.

On Saturday, December 18, Greg Lucini looked out his kitchen window at the sweeping view of the Taunton River beyond his yard. A familiar fallen tree branch that rests on the river bottom was visible, as it always is when the tide is low, but the large raptor resting on it was clearly different from the Bald Eagles that often perch there to fish. The enormous size and distinct markings of this bird captivated his attention throughout the weekend, as it set up camp high in the trees on the opposite side of the river and periodically took flight to explore the area’s offerings or catch a meal. Unbeknownst to Greg, some other local bird watchers had also spotted the conspicuous visitor, and had shared the news among local birding networks. When Greg glanced out his window on Monday morning, he was shocked to see what he described as hundreds of people gathered on the riverbank at nearby Dighton Rock State Park. Even if he might have been inclined to dismiss the uncharacteristic crowd of onlookers, their presence from sunrise to sunset on such a chilly winter day piqued his curiosity. He walked over to see what the commotion was all about, observing license plates from Pennsylvania, New York, and all of the New England states.

An excited buzz filled the air as the observers traded information about the bird, its movements along the river, and its unbelievable backstory. They noted that its size dwarfed that of the Bald Eagles sitting on nearby branches, and that the black and white pattern of its plumage and bright yellow-orange toucan-like beak made it stand out like Rudolph in a herd of reindeer – recognizably similar, yet clearly not the same. Curious neighbors mingled with avian enthusiasts and experienced ornithologists, and everyone was friendly and happy to discuss their understanding of the significance of the moment. Greg, who is attentive to the local wildlife surrounding his Berkley home, soon discovered that this unfamiliar visitor that had caught his eye was, in fact, a very long way from home.

What do we know about this bird?

Steller's Sea-Eagles are massive birds of prey that weigh up to 20 lbs. and can have a wingspan of up to 8 feet. In their native habitat, they are coastal birds that feed on fish and small waterfowl, with a preference for large river mouths. They are typically found in the Russian Far East and Southern China, or in northern Japan, where they migrate for the winter. The excitement about this particular bird comes as much from the story of its exceedingly long journey as it does from the unexpected opportunity for the local birding community to see the uncommon species in person. According to Wildlands’ board member, Wayne Petersen, who is the director of the Massachusetts Important Bird Area (IBA) Program for the Massachusetts Audubon Society, several distinctive features of the bird’s plumage indicate that it’s “virtually unequivocal” that it is the same Steller's Sea-Eagle that has been dazzling birders all over North America for over a year!

Countless articles and videos now trace the epic journey that this lone bird has undertaken since it left its distant home last summer. Wayne and others theorize that it may have made its way into North America by island hopping down the Aleutian Island chain from Siberia into mainland Alaska, where it was first spotted along the Denali Highway in August 2020. Seven months later, it is suspected that the same individual was seen and photographed in Texas, before eventually making its way north to New Brunswick, Canada, and then the Gaspe Peninsula on the Saint Lawrence River, in Quebec, this past summer. In November, the adventurous bird was spotted again in Nova Scotia, before it ultimately reappeared in Southeastern Massachusetts in mid-December.

Unconfirmed reports suggest that the eagle may have been in the area of the Lower Taunton River for about a week before the news broke on 12/20/21, but the social media-fueled frenzy about the once-in-a-lifetime sighting took hold among the New England birding community that Monday morning and continued into the days that followed. Since then, word has spread across the country, showing up in local Massachusetts newspapers, on Alaskan radio stations, and in countless media outlets in between– including the Boston Globe, New York Times, Newsweek, CNN and NPR, to name a few.

But, long before most people even realized that they might want to drop everything and make their way to the Taunton River to catch a glimpse of this rare beauty, the Steller's Sea-Eagle had already taken off for parts unknown. By Tuesday morning, when the adoring crowds arrived again, the bird was gone. And though many people searched the skies of Southeastern Massachusetts throughout the week, sadly, the celebrity eagle did not return. (Remarkably, it was spotted again a week later…this time in the vicinity of Georgetown, Maine).

Why did it end up here?

While the unlikely path of this avian odyssey makes for a pretty interesting story in itself, many people are still wondering: why did it end up here? To address that question, Wildlands’ board members offer two explanations: one scientific, the other hypothetical.

Wayne explains that this bird undoubtedly fits the definition of “avian vagrancy,” which is when a bird is found considerably beyond its usual range. He says most cases of vagrancy can be attributed to either storms, such as hurricanes, or a faulty inherited navigation system that causes persistent disorientation for the bird. To explain this, he uses the counterexample of a robin that builds a nest under the same porch year after year. In this case, the bird demonstrates strong home site fidelity and also winter site fidelity, which allows it to find its way back to those two places using a similar path year after year. Given the distance traveled and the probable time elapsed since the vagrant eagle was last in its home territory, Wayne feels confident that the bird most likely lacks the inherent ability to polarize its nesting home territory and its proper wintering location to allow it to navigate back and forth between the two. He adds, “It clearly has an ability to navigate…but simply not to the right places. It likely has a faulty orientation system that didn’t let it know to go to northern Japan in the winter.” Because of this, he says, it is unlikely (though not impossible) that the bird may ever find its way back to where it belongs. It is homeless and appears to be unequipped with the tools needed to correct its course.

And while this reality tugs at the heartstrings of those following the eagle’s journey, all hope is not lost for this bird. It has been determined to be an adult, based on specific characteristics of its plumage. Wayne notes that, “Despite having a serious problem of seemingly not knowing where to go, it clearly has an ability to navigate from place to place, and an ability to catch fish and scavenge carrion along the way.” He adds, “It can’t get to be this age (at least four years-old) without doing so.” Caught up in the bird’s plight, some have asked if it would be possible to catch it and transport it back to where it belongs. Wayne’s answer to this is two-fold. First, he points out, “It’s not as simple as setting up a net at a bird feeder to capture a raptor that’s practically the size of a Volkswagen”-- the task would be challenging. But, beyond that, he says, “Even if it could be done, it might not stay there anyway, and would possibly end up in the same situation again because of its faulty orientation system. We can reasonably assume that it would likely be significantly handicapped in its ability to stay on track in the future.” This eagle is clearly a survivor, however, and authorities have determined that it should best be left to continue on its way without interference. Whatever direction it may go, the bird’s final chapter is probably yet to be written.

Whether the Steller's Sea-Eagle finds its way back to where it started or continues to accumulate worldly adventures is a question that only time will answer. But the matter of where the bird is likely to be seen next brings us back to Greg Lucini’s thoughts about why, of all places, it decided to visit his backyard in Berkley, MA. According to Greg, he can’t help but think that the bird’s chosen location was not entirely arbitrary, and that the Taunton River and its surrounding conservation lands made for an opportune landing spot. In 2009, the river was nationally designated by Congress as a Wild and Scenic River, for its “outstanding resource values,” which include–among others–ecology and biodiversity.

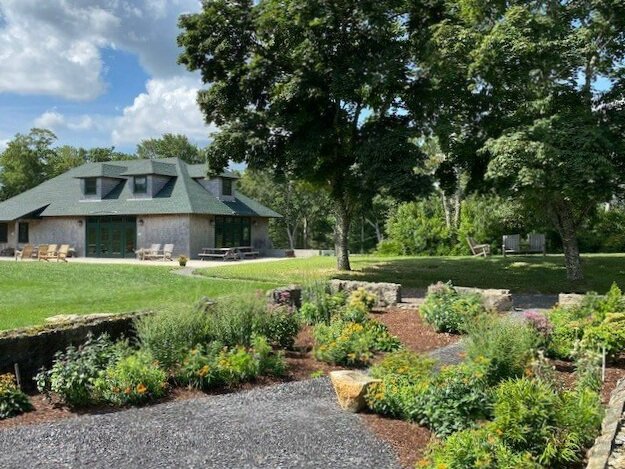

For more than two decades, Wildlands Trust has been instrumental in preserving land around the lower Taunton River, partnering with private landholders, towns, other non-profit organizations, and state entities such as the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game. In the immediate vicinity of the eagle’s temporary home, Wildlands holds a conservation restriction on privately owned land, owns and manages two preserves, including the 77-acre Puddingstone Preserve, contributed to the expansion of neighboring Dighton Rock State Park, and assisted with DCR’s acquisition of what is now Sweets Knoll State Park, located about one mile upstream, in Dighton.

From the perspective of a local landowner who fully appreciates the many natural assets of the Lower Taunton River, Greg believes that the abundance of wildlife – including the presence of several Bald Eagles that have taken up residence along the river in recent years – may have provided somewhat familiar faces to attract the Steller’s Sea-Eagle, while the thriving ecosystem of the undeveloped land offered a conducive environment for the visitor to pause along its journey.

Of course, we’ll never really know why this famous feathered traveler decided to grace us with its majestic presence last month. But we’d like to think, like Greg, that Wildlands’ efforts to preserve ecologically significant landscapes and provide habitat for various wildlife species could have been a contributing factor in the Steller's Sea-Eagle’s decision to visit Southeastern Massachusetts.