A bee rests on a dahlia in the Community Garden at Davis-Douglas Farm.

By Marilynn Atterbury, Key Volunteer

With the first day of spring right around the corner, green thumbs across Southeastern Massachusetts are twiddling with excitement. Gardeners are already dreaming of the flowers and produce that will revitalize their eyes, noses, and tongues after a long, dark winter.

But in early spring, protect the pollinators that sustain your garden and local ecosystem by leaving busyness to the bees. Believe it or not, the best thing you can do for your pollinator garden right now is nothing at all!

Many pollinators, especially bees and butterflies, spend the winter nestled in garden debris. If you rake up those pesky leaves too soon, you will literally be throwing away this year’s pollinators. Wait until the weather warms to a consistent 50 degrees—usually in late March or early April—for your garden clean-up.

Another early-spring tip: bees wake up hungry! So, make sure to plant early-blooming flowers, such as bleeding heart, lungwort, or ajuga. Even a little sugar water will help.

And don’t forget a water source: a shallow dish with flat rocks (for butterfly perching habitat) will do nicely.

Follow these simple tips this spring, and soon your gardens will be alive with pollinators!

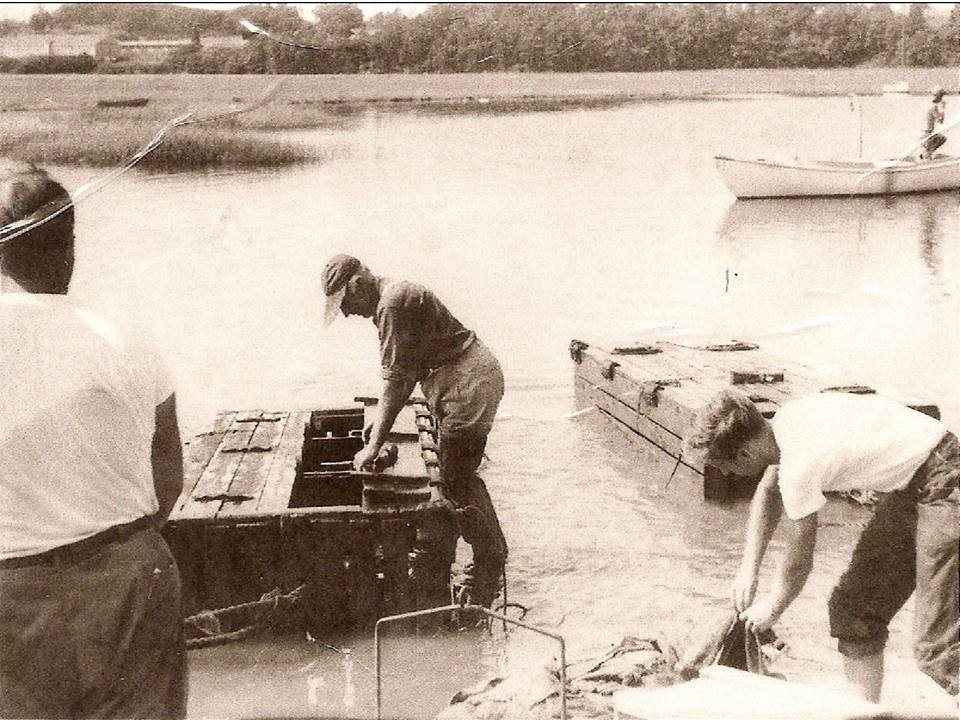

Marilynn (center) helps two high school students restore the Community Garden during Summer of Service.

Marilynn is a primary gardener at Davis-Douglas Farm, and the founder of our pollinator garden. She is also a Wildlands board member, Adopt-a-Preserve lead volunteer, event decorator, and more! Say hello the next time you visit our Plymouth headquarters.